For eight centuries, my people, the Darkhad, have protected the relics of the Mongol Son of Heaven.

I am now 48 years old. When I was a very young man, my father always reminded me of what it meant to be a Darkhad, and how important it was to carry on the sacred duty our forefathers had bequeathed us: guarding the eight white yurts that house the Great Khan’s relics. His fourth son, Tolui, first had these portable mausoleums built on the Mongolian grasslands.

People have always been curious about where Genghis Khan’s final resting place is located. Every few years, the media jumps on a new story reporting the discovery of his tomb. However, these stories only underline the outside world’s limited understanding of Mongol culture.

Traditional Mongolian shamanism espouses that every living being has a soul. When a person dies, their soul does not die with them; instead, it lives on in the objects they used during their lifetime. Therefore, we the Darkhad believe we guard the living soul of the Son of Heaven.

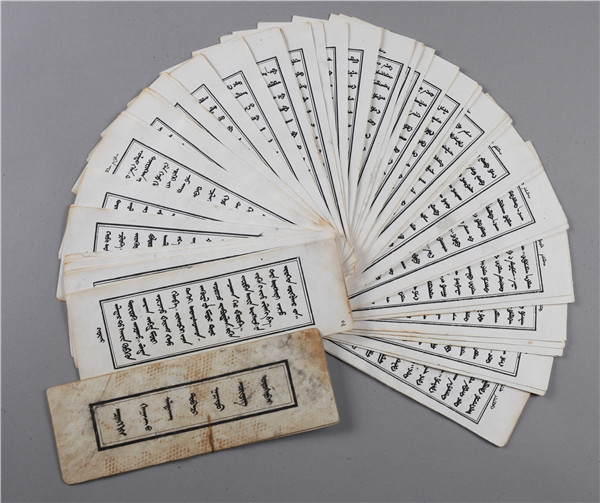

It is said that as Genghis Khan lay on his deathbed, a shamanic doctor plucked a hair from the forehead of a white male camel and placed it in his mouth. After the fur absorbed Genghis Khan’s last breath, the shaman placed it in a bag as a token of his soul. In Mongolian, we call this event the cindariin hurrcag.

However, we are not sure whether the strand of camel hair is actually contained within the eight white yurts. The Darkhad have never fully opened the box to check, as we believe that doing so is to court disaster. We may only open the box a tiny crack on the fifth day of our Spring Festival sacrifice, and then we must shut it again.

Easily transported, the eight white yurts are a testament to our nomadic lifestyle, to Mongolian spiritualism, and to the local environment. They ensure that people across the steppe can continue offering sacrifices to their ancestors. Their mobility also allows the Darkhad to respond flexibly in times of disaster or threat.

Genghis Khan is not only a deity in the minds of the Mongolian people; to the Chinese as well, he is a highly respected ruler. The Yuan dynasty of the 13th and 14th centuries, established by Genghis Khan’s grandson, Kublai, is accepted as a period of so-called native Chinese rule, despite the fact that its imperial line originally hailed from the steppes beyond the country’s northern border. For his part, Genghis united the disparate Mongolian tribes and captured a vast swath of northern China from the enervated Jin dynasty.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese attempted to commandeer the yurts as a means to subdue China’s Mongolian population, but they were met with fierce resistance. To protect the holy relics from destruction, the Darkhad people asked the ruling Nationalist government to move the yurts westward.

In 1939, the government dispatched a military escort to relocate the coffin and its relics to Gansu province in northwestern China. During their passage through Yanan, a Communist Party stronghold, people from all political backgrounds participated in a mass memorial service. They even constructed a memorial hall complete with a personal dedication from Chairman Mao himself.

After 14 years which saw the reunification of China under Communist Party rule, the relics of Genghis Khan were sent back to the Ordos region of Inner Mongolia. With the completion of the official Mausoleum of Genghis Khan in 1956, relics from across Ordos, including portraits, spear-shaped sulde totems, swords, and saddles, were gathered in the city of the same name. This made the once-mobile sacrificial customs performed by the Darkhad and the Golden Family — Genghis Khan’s direct descendants — fixed, centralized, and open to the public.

No matter the course that history has taken, the Darkhad people have always been entrusted with protecting Genghis Khan’s spirit through the ages. When his mausoleum was built, the local authorities delegated eight Darkhad people to organize daily offerings of food, alcohol, and incense, and to watch over the relics. In return, they received food and money. Today, the mausoleum remains primarily under the supervision of the Ordos tribe of the Mongol ethnic group, with Darkhad members in leadership positions.

For the Darkhad, the Ordos region’s recent flourishing economy is a blessing from Genghis Khan’s spirit. It signifies that our regional leaders have paid Genghis Khan due respect through their offerings. In return, his spirit is allowing the Ordos people to prosper.

However, economic prosperity brings its own problems, particularly through conflict with traditional culture. Today, Ordos relies on the cultural resources of Genghis Khan’s mausoleum to foster the development of the tourism industry. As a result, his mausoleum — sacred ground to the Mongolian people — has naturally become a popular stomping ground for visitors.

But non-Mongolians come to the area only for travel, and they often don’t understand the full significance of Genghis Khan to us. Sometimes, when they see us in traditional dress making real sacrificial offerings, they think it’s all for show.

We can only insist on hosting the rituals for Genghis Khan. These include daily and monthly offerings, weekday sacrifices of mutton and goat meat, larger festivals during the Year of the Dragon or the Year of the Snake, and other diverse, rich ceremonies.

Day after day, the Darkhad work tirelessly at the mausoleum. My role is to lead the rituals. I oversee use of the various sacrificial vessels, prepare and arrange the ceremony, and chant the traditional odes in homage to Genghis Khan.

We have the highest regard for all those who have visited the cemetery of Genghis Khan, but religious believers and ordinary travelers are treated differently. The former enter the mausoleum free of charge, with their status ranked according to the type and size of their offerings. The latter, meanwhile, have to pay for tickets. Preferential treatment — such as priority in making offerings, chanting blessings, and so on — is given to Ordos residents.

Price alone does not determine the value of the offering. For instance, a bottle of good maotai liquor costs far more than an entire sheep, but liquor does not merit the same blessings because Mongolians regard a whole sheep as a higher form of ceremony meant only for grand occasions. Mutton also doubles as food that the Ordos tribe — especially those of Darkhad lineage — serves only to distinguished guests.

Of course, we all recognize that times are changing. Of the approximately 6,000 Darkhad people alive today, many are no longer guardians. Instead, we are academics, government officials, farmers, herdsmen, private landowners, and much more. However, for some of us, certain things are constant: We try to remain steadfast in our beliefs and to worship our gods in the hope that they will bless us as their loyal subjects.

(Header image: The traditional winter ceremony at the Mausoleum of Genghis Khan in Ordos, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Nov. 14, 2015. Courtesy of the Mausoleum of Genghis Khan)