This time I would like to draw your attention to one of my favourite blogs at the one hand and one of my favourite actors on the Silk Road at the other hand.

Read this article by Llewelyn Morgan in "

Lugubelinus" on

Sir Aurel Stein and in particular on his dog(s) Dash!

![Dash in Afgh]()

A full-scale dog-blog was always on the cards. I came quite close in

this one, when a figure in a photo I’d been shown turned out to be a pioneer of Afghan Hound breeding. But this blog is devoted to a single dog, a fox terrier called Dash who belonged to the archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein.

Actually Stein owned seven dogs in succession, and every one of them was called Dash. The name was more common at one time than it seems to be now: Queen Victoria’s

Dash was a King Charles spaniel. It still seems slightly odd to give every one of a sequence of dogs the very same name, and Stein, whose claim to fame is above all as an investigator of the Buddhist cultures of Central Asia, sometimes toyed with the idea that the latest Dash was a reincarnation of one of its predecessors.

Anyhow, the subject of this blog is Dash II, or “Dash the Great” as Stein liked to refer to his very favourite of them all; he also called him Kardash Beg, “The Honourable Snow Companion”, when he discovered with delight that his new dog had a relish for snow. Pets belonging to Aurel Stein could expect to encounter some pretty gruelling climatic conditions.

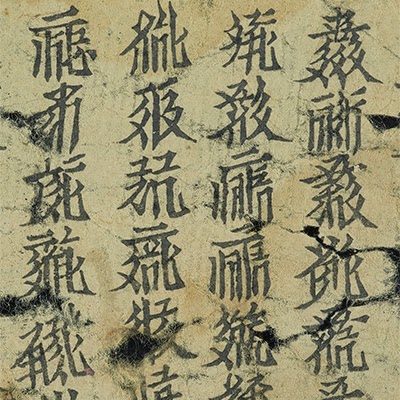

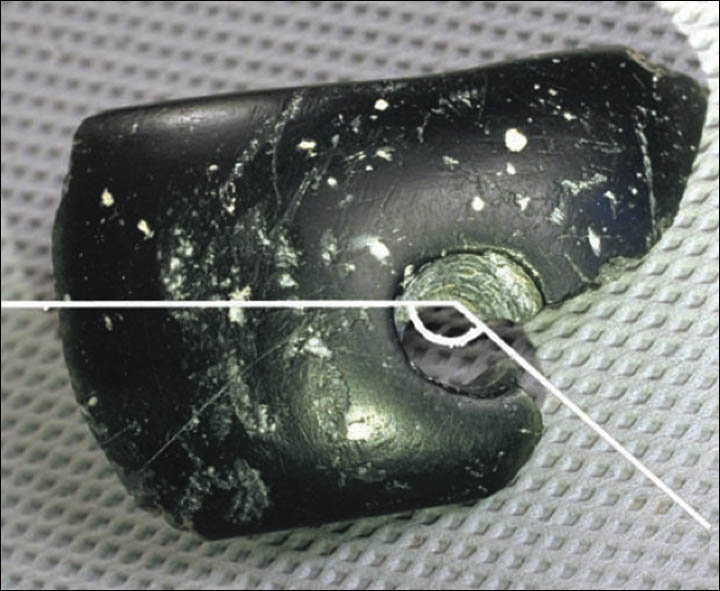

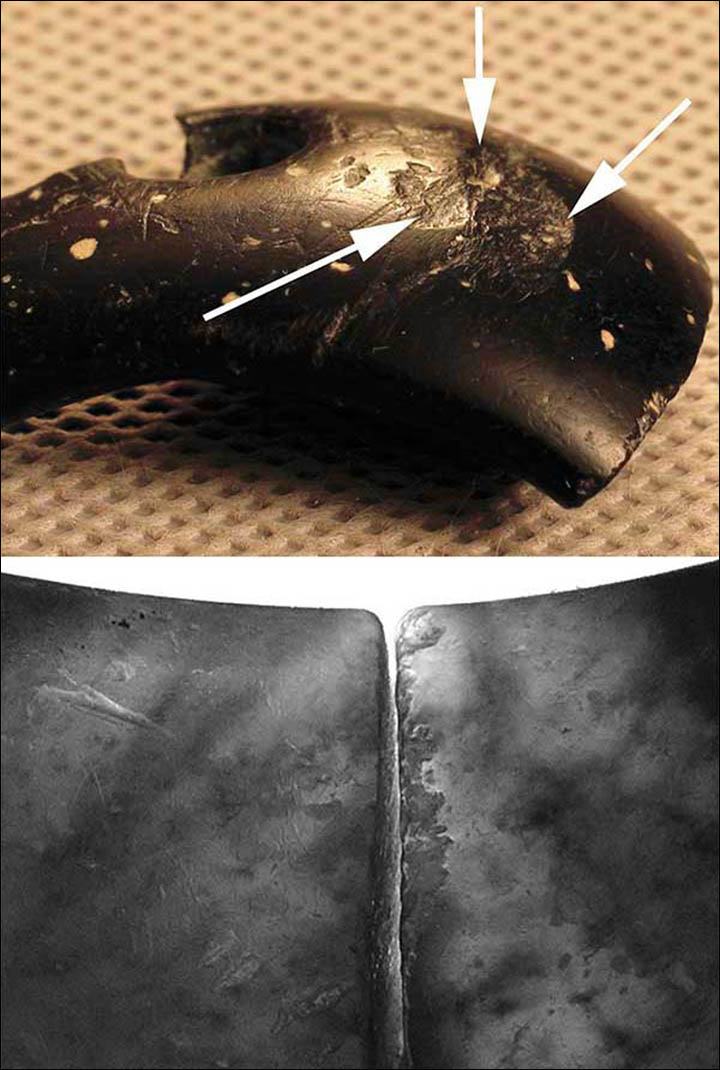

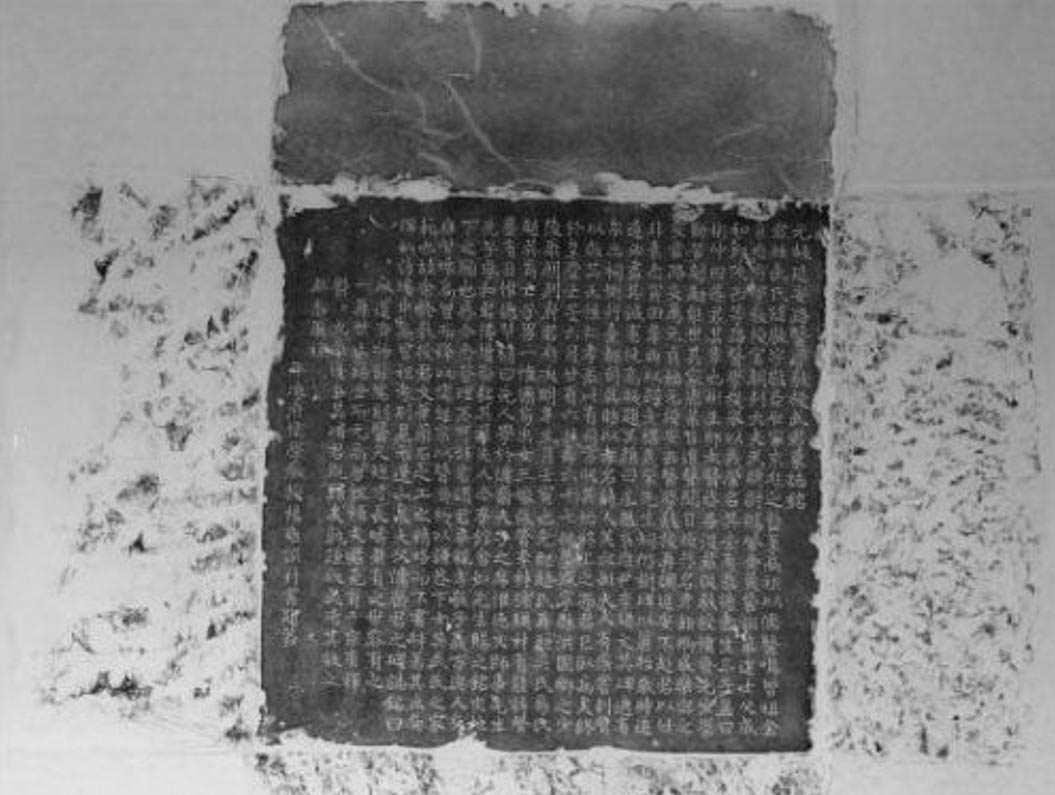

Stein acquired Dash the Great in 1904, and the dog accompanied him on his Second Expedition into Central Asia from 1906 to 1908, Stein’s most audacious, most successful, and ultimately most controversial venture into Chinese Turkestan. It was during this expedition that Stein was able to investigate a trove of Buddhist material in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang, removing a large quantity of texts, textiles and paintings. But earlier in the expedition he and his team had made the high-altitude crossing from the very northeastern tip of Afghanistan into Chinese Central Asia, and later he undertook a perilous, and very nearly disastrous, crossing of the Taklamakan desert.

Dash is a regular presence in Stein’s accounts of his expedition, especially the popular

Ruins of Desert Cathay (1912), often most visible in moments of particular intensity. As things become very desperate during Stein’s crossing of the Taklamakan desert, his men threatening to mutiny, he is grateful that Dash makes do on “a saucerful [of water] spared from my cup of tea”. As they scale the 16,000-foot Wakhjir pass between Afghanistan and China, the generally irrepressible terrier whimpers with the cold and insists on sheltering beneath Stein’s fur coat. On another occasion he’s roused from sleep in Stein’s tent by the excitement of Stein and Chiang-Ssu-yeh, Stein’s “Chinese secretary and helpmate”, when they find proof that

the frontier fortifications they’re investigating date from as early as the first century AD.

Dash chases marmots in the high country, “distinctly provoking for so indefatigable a hunter”, develops a knack of mounting a horse, “jumping up to the stirrup, and thence to the pommel of whoever was offering him a lift”, and gets badly mauled by a pack of semi-feral sheepdogs. When the party finds itself having to cross the Kash river over a ridiculously makeshift bridge, the poor thing is trussed up in a bag and passed along a wire rope along with the rest of the baggage.

![image]()

The expedition took its toll on Stein. As he crossed back into India in 1908 he suffered frostbite while surveying at high altitude, losing several toes of his right foot after being carried down in agony to Ladakh. When he was eventually fit enough to travel, he describes his departure for Britain at the end of 1908 and enforced separation from Dash, “the last of my faithful travel companions, but, perhaps, the nearest to my heart”: dogs were not allowed on the P. & O. Mail boat. Dash made his own way to Britain on a separate steamer, spent four months in quarantine, and “was joyfully restored to his master under Mr P. S. Allen’s hospitable roof at Oxford.”

P. S. Allen was a Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, and he and his wife Helen were scholars of Erasmus and two of Stein’s oldest and closest friends; their “hospitable roof” was 23 Merton St., where Stein always stayed on his visits to Britain, and where Dash would actually spend the rest of his life. Stein seems to have decided that his “inseparable little companion” had had enough adventure. At any rate, when he returned to India he left Dash behind with the Allens. The comfortable new home of this canine veteran of the sand and snow deserts of the Taklamakan and Pamir Knot is now part of the Eastgate Hotel.

Dash lived with the Allens for another nine years, and while Merton St. was his home, he was clearly left to wander wherever he liked across Oxford. But as the First World War drew to a close, a new and deadly threat to an increasingly decrepit old dog was being introduced to Oxford’s streets, the motorised Omnibus. Percy Allen wrote to Stein to explain what happened:

He took himself out for a walk one aft. Friday, 27 Sept. [1918], & was run over by a motor bus in Park End St—the street which goes down to the station as the continuation of the High & Queen St. The police brought around his collar next morning, & reported that he had been killed instantaneously, & that they had buried him in their usual place. Helen went to the police station to enquire, as soon as we returned home—10 days later—but by that time it was too late to unearth him & bring him to sleep in the garden where he has so often slept before.

It’s a terribly banal end for a dog who’d seen so much, run over by a bus on Park End St. Soon the regular letters between Stein and the Allens turned back to the urgent issues of the day, the Armistice just a month or so after Dash’s death, and the Spanish Flu. But for as long as Dash is the focus of these letters between old friends, he provokes a touching outpouring of affection between them. Helen Allen reminisced to Stein about Dash’s life in Oxford:

He has been as outstanding amongst dogs, as his master amongst men; such sagacity & such devotion. I can see him in so many different poses: returning on a Cotswold walk after a chase after a hare, to look which way we were gone meanwhile, locating us & then heading straight for our slow plodding figures; looking up full of enquiry when he heard: “Go and meet him, Dash,” & then bounding forward joyously as he caught sight of Percy…

Such faithfulness as he has shown must surely meet a fit reward.

And we send you many thanks for the added happiness you brought into our lives through Dash.

“Surely a Ulysses among dogs,” wrote Percy Allen to Stein:

full of wise counsel & dignity, & greatly attached to his friends. You brought great pleasure into our lives thro’ him: for wh. we thank you, amice noster, as for so much else. Blessings on Dash the Great.

Stein, in response, thanked his friends for their comforting words:

Never before, I feel sure, had a faithful canine companion’s departure been recorded in words more true and deserved. How grateful I feel to [Helen] for having thus softened the pang which this sad news caused me the enclosed letter for her cannot express adequately. I do not command the inexhaustible goodness of soul which is life’s greatest boon in you both, nor that grace of expressive brief words which mature and constant communion with Erasmus have bestowed upon you both. I never cease to give thanks for all the brightness which you two have brought into my existence for the last twenty years—but my gratitude must be equally great for all you have done to help me in facing sad losses and trials.

Well, we all know dogs can be surrogate objects of affection for people who find it difficult to express emotion. Why else are English people so fond of them? In happier times, too, “Dash” had been a vehicle for the Allens’ affectionate pride in their friend’s success, writing a letter to congratulate Stein on the knighthood he received in 1912:

23 Merton St

Bara din 1912

Many congratulations, dear Master. Am wearing my collar of achievement.

If I had known this was coming, I should not have cried on the Wakhjir.

Whip the young one, and keep him in order.

Bow wow

(Have assumed this title) SIR DASH, K.C.I.E.

Still, just a dog.

The following article is from the IDP (International Dunhuang Project) newsletter No. 18 and gives a.o. some more pictures of his dogs:

A Dash Across Asia

In keeping with the animal theme of this newsletter, we have decided to dedicate a page to the history of Sir Aurel Stein's various canine companions — all called Dash and all intrepid travellers with Stein on his Asian expeditions.

![Dash at Niya]()

![The British Library: Photo. 392/23(12) detail]()

Left:Dash I at Niya on Stein's 1st Central Asian Expedition, January 1901. Published in Ancient Khotan fig.38, opp.p. 328

Right:Dash II The British Library: Photo. 392/23(12) detail

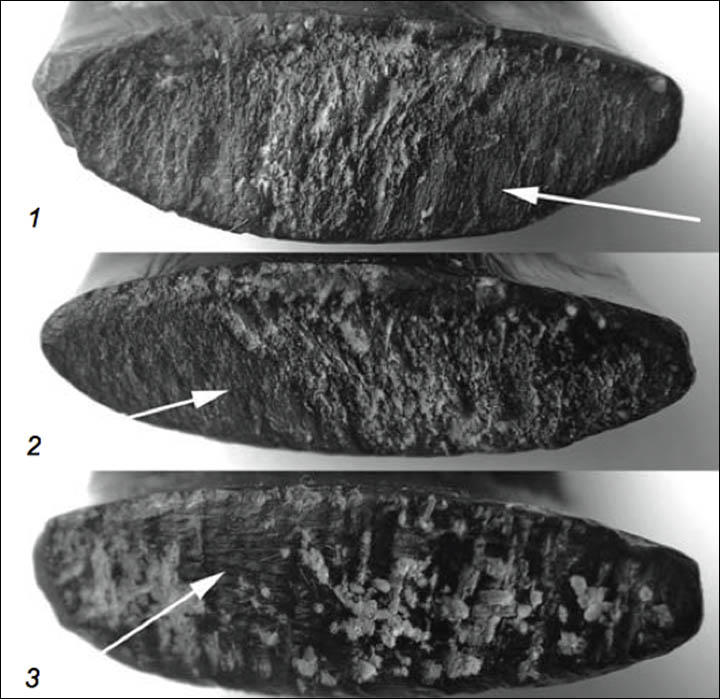

Dash I, Stein's first dog, was acquired in 1896 and accompanied Stein on his early travels, culminating in the 1st Central Asian Expedition. Known also by the Turki name Yolchi Beg — 'Sir Traveller'— given to him by Stein's servant Mirza, he is seen here at Niya in January 1901, wearing the Kashmiri coat specially made to protect him against the desert winter. He died in India in 1902 while Stein was in England.

'Dash the Great', the dog against which all his successors were to be measured, was acquired by Stein in 1904 and travelled with him on the 2nd Central Asian Expedition. He returned to England with Stein in 1909 and lived in retirement in Oxford until 1918, when he was run over by a bus. He is shown here beneath Stein's desk in his camp at Mohand Marg near Srinagar in 1905.

![The British Library. Photo. 392/29(10) detail]()

![The British Library. Photo. 392/47(227) detail]()

Left:Dash III The British Library: Photo. 392/29(10) detail

Right:Dash IV The British Library. Photo. 392/47(227) detail

Acquired by Stein in 1912, Dash II's successor accompanied Stein on the 3rd Central Asian Expedition and is seen here at Jaglot in August 1913. He survived until 1919, when he was killed by a pack of dogs in Srinagar.

Acquired as a puppy in 1921, he was brought back to England by Stein in 1924, but died the following year. He is shown here with Stein in an Oxford garden in September 1925.

![The British Library. Photo. 392/33(4) detail]()

![The British Library. Photo. 392/37(209) detail]()

Left:Dash V The British Library. Photo. 392/33(4) detail

Right:Dash VI The British Library. Photo. 392/37(209) detail

Acquired in 1927, Dash V was the only Dash who was not a fox terrier and is seen here at Srinagar in November 1928. He accompanied Stein on the 4th Central Asian Expedition, but died at Kashgar in 1930. Stein considered that he was perhaps overbred for the rigours of travelling.

Acquired in 1931 and considered by Stein 'a very promising reincarnation of Dash the Great', he travelled with Stein on his archaeological investigations in Iran and Iraq, and is here seen at Kerman, Iran in May 1932. He survived until 1941, when he was killed by a leopard near Mohand Marg.

Acquired 1943. Fate unknown.

Text by John Falconer and images, courtesy of Stein, prepared by Rachel Roberts.

![sauran-drone]() It was one of only a few cities that survived the Mongol onslaught. The city administrators must have learned their lesson from nearby Otrar, which taunted the Mongols and was razed to the ground, with all inhabitants killed. As empires waxed and waned, Sauran adapted, becoming the capital of the Mongol White Horde, and later, a military fortress under Tamerlane.

It was one of only a few cities that survived the Mongol onslaught. The city administrators must have learned their lesson from nearby Otrar, which taunted the Mongols and was razed to the ground, with all inhabitants killed. As empires waxed and waned, Sauran adapted, becoming the capital of the Mongol White Horde, and later, a military fortress under Tamerlane. It was one of only a few cities that survived the Mongol onslaught. The city administrators must have learned their lesson from nearby Otrar, which taunted the Mongols and was razed to the ground, with all inhabitants killed. As empires waxed and waned, Sauran adapted, becoming the capital of the Mongol White Horde, and later, a military fortress under Tamerlane.

It was one of only a few cities that survived the Mongol onslaught. The city administrators must have learned their lesson from nearby Otrar, which taunted the Mongols and was razed to the ground, with all inhabitants killed. As empires waxed and waned, Sauran adapted, becoming the capital of the Mongol White Horde, and later, a military fortress under Tamerlane.

![sauran]() The walls itself are still many meters high in places, crumbling elsewhere, providing an intimate atmosphere where you will be alone with bird song and cute little turtles, free to let your imagination feel up the passage of time. For now, you will be the only visitor. Unconfirmed claims that Tolkien got the name of the evil lord Sauron (from the tribe of Ainur, which is a local Kazakh tribe) from Lord of the Rings from here have not yet led to a boom in hobbit houses. Yet.

The walls itself are still many meters high in places, crumbling elsewhere, providing an intimate atmosphere where you will be alone with bird song and cute little turtles, free to let your imagination feel up the passage of time. For now, you will be the only visitor. Unconfirmed claims that Tolkien got the name of the evil lord Sauron (from the tribe of Ainur, which is a local Kazakh tribe) from Lord of the Rings from here have not yet led to a boom in hobbit houses. Yet. The walls itself are still many meters high in places, crumbling elsewhere, providing an intimate atmosphere where you will be alone with bird song and cute little turtles, free to let your imagination feel up the passage of time. For now, you will be the only visitor. Unconfirmed claims that Tolkien got the name of the evil lord Sauron (from the tribe of Ainur, which is a local Kazakh tribe) from Lord of the Rings from here have not yet led to a boom in hobbit houses. Yet.

The walls itself are still many meters high in places, crumbling elsewhere, providing an intimate atmosphere where you will be alone with bird song and cute little turtles, free to let your imagination feel up the passage of time. For now, you will be the only visitor. Unconfirmed claims that Tolkien got the name of the evil lord Sauron (from the tribe of Ainur, which is a local Kazakh tribe) from Lord of the Rings from here have not yet led to a boom in hobbit houses. Yet.