Studies of the mummified Ukok 'princess' - named after the permafrost plateau in the Altai Mountains where her remains were found - have already brought extraordinary advances in our understanding of the rich and ingenious Pazyryk culture.

The tattoos on her skin are works of great skill and artistry, while her fashion and beauty secrets - from items found in her burial chamber which even included a 'cosmetics bag' - allow her impressive looks to be recreated more than two millennia after her death.

Now Siberian scientists have discerned more about the likely circumstances of her demise, but also of her life, use of cannabis, and why she was regarded as a woman of singular importance to her mountain people.

Her use of drugs to cope with the symptoms of her illnesses evidently gave her 'an altered state of mind', leading her kinsmen to the belief that she could communicate with the spirits, the experts believe.

The MRI, conducted in Novosibirsk by eminent academics Andrey Letyagin and Andrey Savelov, showed that the 'princess' suffered from osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone or bone marrow, from childhood or adolescence.

Close to the end of her life, she was afflicted, too, by injuries consistent with a fall from a horse: but the experts also discovered something far more significant.

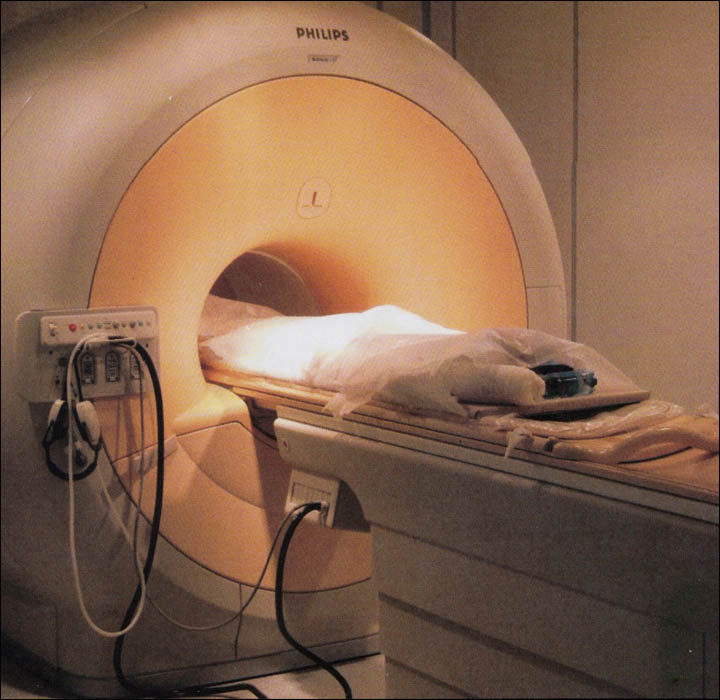

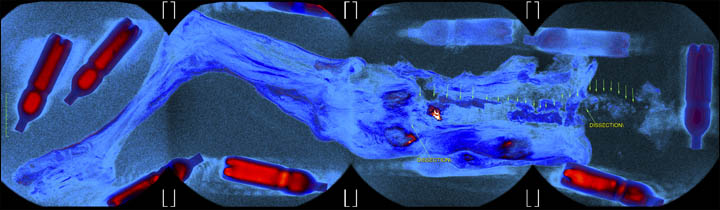

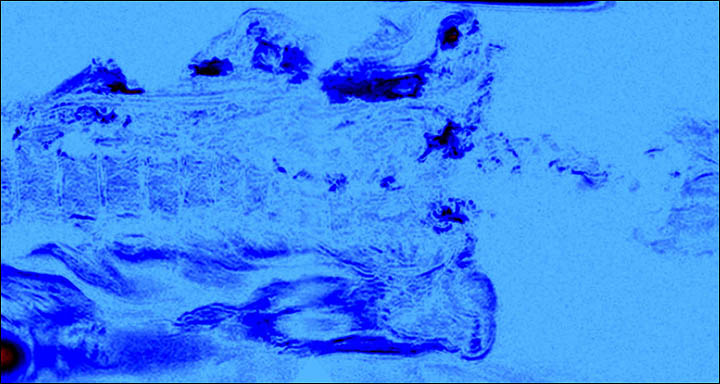

MRI scanning of 'Princess Ukok' mummy (top). General views (bottom). Pictures: 'Science First Hand', Andrey Letyagin

'When she was a little over 20 years old, she became ill with another serious disease - breast cancer. It painfully destroyed her' over perhaps five years, said a summary of the medical findings in 'Science First Hand' journal by archeologist Professor Natalia Polosmak, who first found these remarkable human remains in 1993.

'During the imaging of mammary glands, we paid attention to their asymmetric structure and the varying asymmetry of the MR signal,' stated Dr Letyagin in his analysis. 'We are dealing with a primary tumour in the right breast and right axial lymph nodes with metastases.'

'The three first thoracic vertebrae showed a statistically significant decrease in MR signal and distortion of the contours, which may indicate the metastatic cancer process.'

He concluded: 'I am quite sure of the diagnosis - she had cancer. She was extremely emaciated. Given her rather high rank in society and the information scientists obtained studying mummies of elite Pazyryks, I do not have any other explanation of her state. Only cancer could have such an impact.

![Ukok mummy MRI scan Ukok mummy MRI scan]()

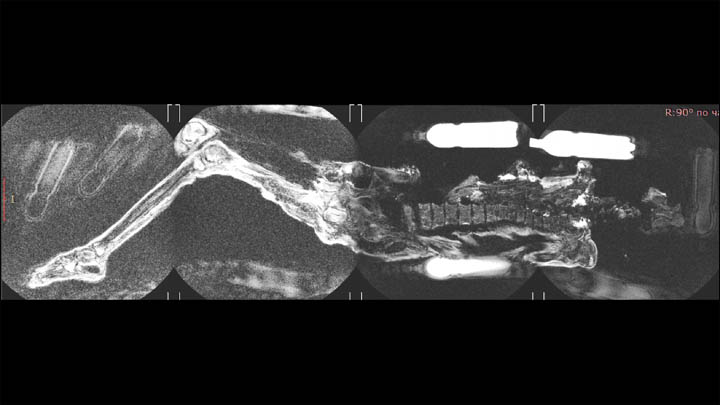

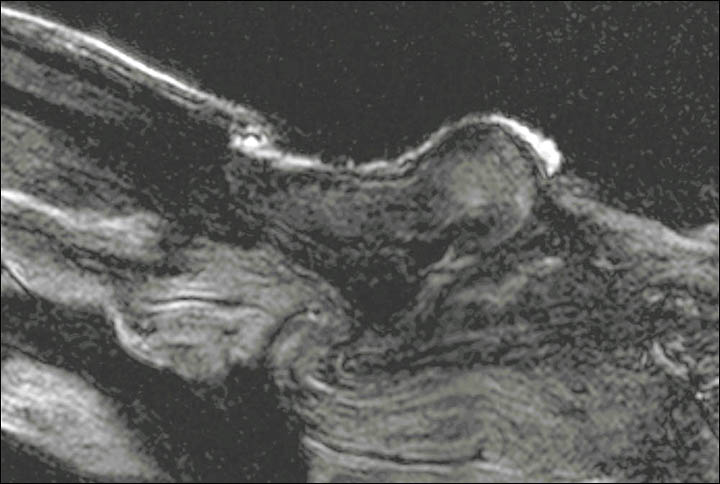

Dr Andrey Letyagin; scans show right breast tumor and metastatic lymph nodes in the right axilla and metastases in the spine, surrounded by edematous paravertebral fiber (bottom). Pictures: The Siberian Times, Andrey Letyagin

'Was it the direct cause of the death? Hard to say. We see the traces of traumas she got not so long before her death, serious traumas - dislocations of joints, fractures of the skull. These injuries look like she got them falling from a height.'

But he stressed: 'Only cancer could have such an impact. It is clearly seen in the tumour in her right breast, visible is the metastatic lesion of the lymph node and spine...She had cancer and it was killing her.'

While breast cancer has been known to mankind since the times of the Ancient Egyptians, a thousand years before it was recorded by Hippocrates, father of modern medicine, this is a unique case of the detection of the disease using latest technology in a woman mummified by ice.

Dr Letyagin is from the Institute of Physiology and Fundamental Medicine, and Dr Savelov, an associate in the laboratory of magnetic resonance tomography at the International Tomography Centre, both of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Medical Science, both in Novosibirsk.

From their work and other data, for example the last food found in the stomachs of horses buried alongside the ancient woman, Dr Polosmak has formulated an intriguing account of her final months hundreds of years before the birth of Christ.

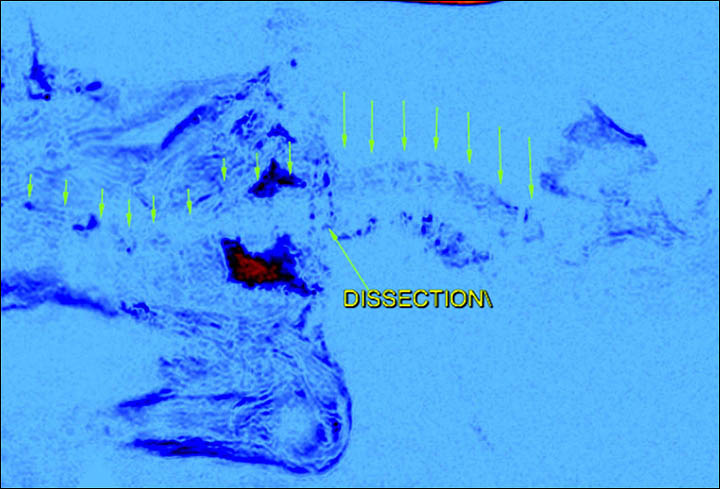

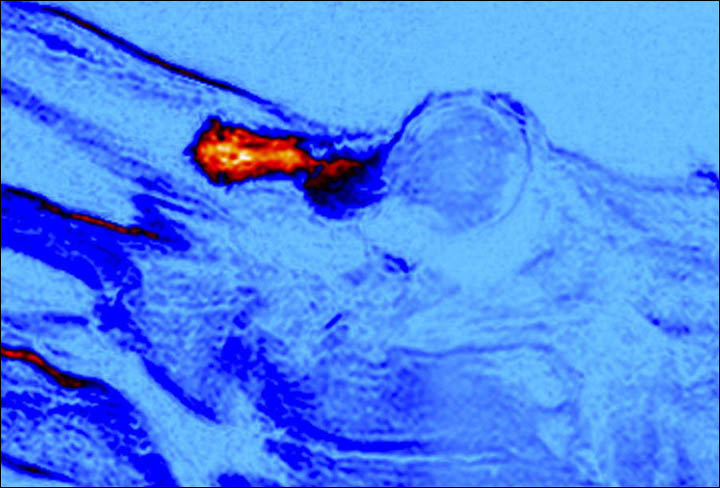

'Princess Ukok' mummy in Anokhin museum, Gorno-Altaisk and, below scans of the dislocated right hip, with bright red color marking edematous tissue in right inguinal area. Pictures: Alexander Tyryshkin, Dr Andrey Letyagin

'When she arrived in winter camp on Ukok in October, she had the fourth stage of breast cancer,' she wrote. 'She had severe pain and the strongest intoxication, which caused the loss of physical strength.

'In such a condition, she could fall from her horse and suffer serious injuries. She obviously fell on her right side, hit the right temple, right shoulder and right hip. Her right hand was not hurt, because it was pressed to the body, probably by this time the hand was already inactive. Though she was alive after her fall, because edemas are seen, which developed due to injuries.

'Anthropologists believe that only her migration to the winter camp could make this seriously sick and feeble woman mount a horse. More interesting is that her kinsmen did not leave her to die, nor kill her, but took her to the winter camp.'

In other words, this confirmed her importance, yet though she is often called a 'princess', the truth maybe she was was - in fact - a female shaman.

'It looks like that after arriving to the Ukok Plataue she never left her bed,' she said. 'The pathologist believes that her body was stored before the funerals for not more than six months, more likely it was two-to-three months.

'She was buried in the middle of June - according the last feed that was found in the stomachs of horses buried alongside her. The scientists think that she died in January or even March, so she was alive after her fell for about three to five months, and all this time she lay in bed.'

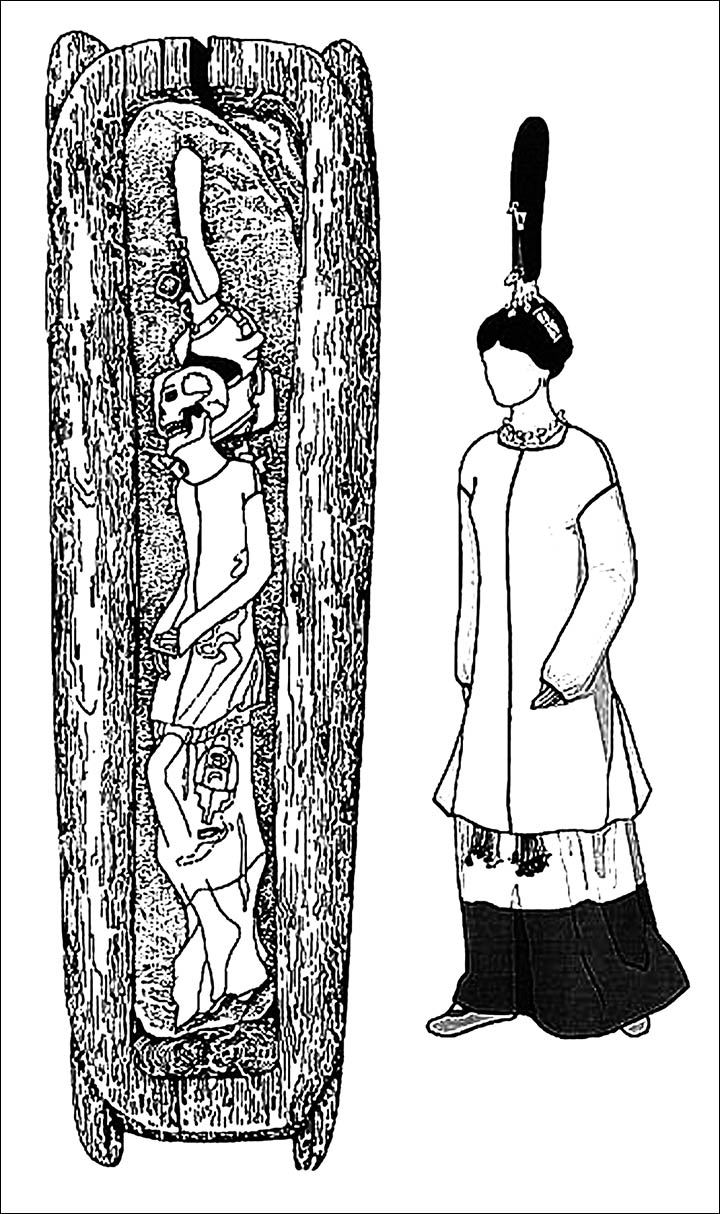

Scheme of the burial and reconstructions of Pazyryk woman's and man's costumes. All items were found inside 'Princess' Ukok burial. Reconstruction by D. Pozdnyakov, Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Science. A sculptor's impression of how Princess Ukok looked 2,500 years ago (bottom)

Dr Polosmak says we should pay 'special attention' to 'the fact that likely she used some analgesics, with all the ensuing consequences.

'In ancient cultures, from which there is a written testimony, such analgesics were used wine, hashish, opium, henbane, an extract of mandrake, aconite and Indian hemp. The Pazyryks knew hemp and its features.'

It is known that in her burial chamber was a container of cannabis.

'Probably for this sick woman, sniffing cannabis was a forced necessity,' said the scientist. 'And she was often in altered state of mind. We can suggest that through her could speak the ancestral spirits and gods. Her ecstatic visions in all likelihood allowed her to be considered as some chosen being, necessary and crucial for the benefit of society. She can be seen as the darling of spirits and cherished until her last breath.'

Evidently, shamans could often assume their powers after a significant illness: a woman might be physically weakened but able to develop her powers of concentration and meditation. This would explain the care her people took to care for her and not leave her to die, or hasten death. It also helps to understand the way her burial was conducted in a style similar - but different - to royalty.

Princess Ukok as the ice melted, with marked tattoos on her fingers; picture and drawing of tattoos on her shoulder. Pictures: Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Science

She was buried not in a line of family tombs but in a separate lonely mound, located in a visible open place. This may show that the Ukok woman did not belonged to an exact kin or family, but was related to all Pazyryks, who lived on this lofty outpost, some 2,500 metres above sea level.

This is an indication of her celibacy and special status. Besides, three horses were buried with her. In a common burial, one would be sufficient.

Dr Polosmak has described how the jewellery in her grave was wooden, and covered with gold, so not of the highest quality of the period. Yet there was a strange and unique mirror of Chinese origin in a wooden frame. There were also coriander seeds, previously found only in so-called 'royal mounds'. Her mummification was carried out with enormous care in a comparable manner to royals.

Significantly, in the Altai Mountains, her supernatural powers are seen as continuing to this day. Elders here voted in August to reinter the mummy of the ice maiden 'to stop her anger which causes floods and earthquakes'.

Known to locals as Oochy-Bala, the claim that her presence in the burial chamber was 'to bar the entrance to the kingdom of the dead'. By removing this mummy, the elders contend that 'the entrance remains open'.

They are demanding that she is removed from a specially-built museum in the city of Gorno-Altaisk, capital of the Altai Republic, and instead reburied high on the Ukok plateau.

'Today, we honour the sacred beliefs of our ancestors like three millennia ago,' said one elder. 'We have been burying people according to Scythian traditions. We want respect for our traditions'.

See related: