Genghis Khan, unlike most Mongols in history, is a household name, regularly misappropriated as a right-wing totem. If we recall the genocidal killing sprees of, say, Stalin and Mao, perhaps it would be more historically accurate to say ‘to the left of Genghis Khan’. In the popular imagination he is the despot’s despot, a one-man killing machine who led his army of mounted archers to triumph after triumph, terrorising and slaughtering by the million to carve out an empire that stretched from the Caspian to the Pacific. His martial conquests place him in the top trio of world conquerors, alongside Alexander the Great and Tamerlane.

If you had the misfortune to live in Central Asia during Genghis’s rampages in the 1220s, you ran the very real risk of being cut in two, beheaded, disemboweled, perhaps even forced to swallow molten metal by his ferocious soldiers. Cities were razed and depopulated, prisoners slain or ordered to march as a shield before the army, in full battle formation. Mongol bloodlust was such that even cats and dogs were killed.

Yet the same man who is said to be responsible for the deaths of a world record 40 million is also noted — admittedly less widely — for his religious tolerance, enlightened diplomacy and championing of women’s rights. As Edward Gibbon noted,

The Catholic inquisitors of Europe who defended nonsense by cruelty, might have been confounded by the example of a barbarian, who anticipated the lessons of philosophy and established by his laws a system of pure theism and perfect toleration.

Gibbon went so far as to posit ‘a singular conformity’ between the religious laws of Genghis and those of John Locke.

Genghis was convinced of his divinely ordained calling to subdue and rule an unruly world, a view accepted by John Man and faithfully maintained by many Mongols today. During the past few months I have received more than 50 impromptu emails from an eccentric young Genghis disciple in Mongolia who told me how he had preserved some of his father’s ashes in fermented mare’s milk and travelled right across the country to sprinkle them over Genghis’s birthplace, honouring him as the father of the nation.

Unlike Tamerlane, whose empire collapsed in short order on his death in 1405, Genghis bequeathed an empire that would endure and expand, and this is Man’s great interest here. He is rightly fascinated by one descendant of the great tyrant in particular: Genghis’s grandson Kublai, generally remembered only as the mysterious potentate in Coleridge’s opium-enhanced poem ‘Kubla Khan’, resident of Xanadu and possessor of a ‘stately pleasure dome’.

Kublai hailed from a junior branch of the family and only managed to take supreme power as Great Khan thanks to his spirited mother and his own diplomatic and military prowess. The sudden and successive deaths of Kublai’s brothers Ariq, Hulagu, Berke and Alghu within the space of a few months from 1264 fortuitously opened the path to power, allowing him to settle and then expand his dominions in the east.

In short order Kublai became the richest and most powerful man on earth. His conquest of China and its deftly handled assimilation into a Mongol-Chinese empire was surely his greatest achievement. In 1271, only seven years after establishing his imperial capital at Xanadu, he shifted his headquarters to Beijing, where his taste for grandeur was given free rein in a remarkable building programme that gave birth to the Imperial City. Man clearly enjoys the delightful fact that China’s current borders were determined not by a Chinese ruler but by a Mongolian warlord.

He does a splendid job of conveying the sheer opulence and grandeur of Kublai’s court, not least the hunting. For 500 kilometres or 40 days’ journey from his new capital the entire countryside was dedicated to hunting. The large game belonged to the emperor: boar, deer, elk, wild asses and wildcats, expertly marshaled to their destruction by 2,000 dog handlers and 10,000 falconers. The figures are Marco Polo’s, and therefore extremely suspect, but you get the point.

Much of this is familiar material and may even be familiar to readers of Man’s earlier works, which include accessible biographies of both Genghis and Kublai. If Mongol history is your thing, David Morgan (The Mongols), Igor de Rachewiltz (The Secret History of the Mongols) or Henry Howorth (History of the Mongols) are surer guides. What Man does, however, is tell a rollicking good story, his historical narrative interspersed with high-spirited travel-writerly digressions, searching for Genghis’s secret burial place one minute, positing a slightly fanciful link between Genghis and Columbus the next. The personal tone is lively and engaging, Man’s wide travels recorded in a series of handsome illustrations.

Man leaves us with a final playful thought which suggests Beijing publishers may not be rushing to have this book translated. For the Chinese, Genghis and Kublai made Mongolia part of China. For Mongols, however, they were the great leaders who made China part of Mongolia.

This article first appeared in the print edition of The Spectator magazine, dated

12 July 2014- This the review in the Daily Mail of July 3, 2014

- Genghis Khan has been a byword for barbarity for the last 800 years

- Some historians estimate four million people were killed under his orders

- As a boy Genghis believed God had decreed he should conquer the land

- The name Genghis means 'fierce, hard, tough'

- During Genghis's reign of terror the Mongol Empire took up most of Asia

PUBLISHED: 22:11 GMT, 3 July 2014 | UPDATED: 09:45 GMT, 11 July 2014

THE MONGOL EMPIRE by John Man (Transworld £20)

As a byword for barbarity, Genghis Khan has come down to us 800 years later as the cruellest conqueror of all time. We preserve his name to compare the perpetrators of genocide today to him.

Is this tradition justified? That is what a new biographer should tell us and this one, John Man, has every qualification. He even speaks Mongol and makes Mongolia his stamping ground. He has written a very lively and enjoyable book on a very complex and baffling story.

It is littered with names that you have never heard of and cannot pronounce, and the two you do know are not as you thought: Genghis starts a soft G — Chinghis — and his grandson was Kublai Khan, not Kubla as Coleridge had it.

Barbaric: Genghis Khan's name has lived on for 800 years because of the mass killings that took place under his command

The first chapters tell how a poor, illiterate boy, originally called Temujin, got himself recognised as leader of the hitherto disunited Mongols. This near-pagan lad had one great conviction: that Tengri, the Mongol deity, had decreed that he was to conquer all the land in every direction. Why he believed this is a mystery.

He set about it and every victory which he and his horsemen achieved confirmed his belief that God was on his side. In 1189 the Mongols decided he should have a new name: Genghis. It was unique and until recently no one could explain where it came from. Now, however, scholars believe it derives from an obsolete Turkish word, chingis, meaning ‘fierce, hard, tough’.

The Mongols took naturally to the idea that they were the master race. Under Genghis — The Fierce Ruler — their empire swelled like a pregnant pig, swallowing up most of central Asia from the Caspian Sea in the west to the China Sea in the east, and taking in the great cities of the Silk Road, Bukhara and Samarkand.

In the spring of 1211, he gathered an army some 100,000 strong and advanced across the Gobi to conquer the Chinese empire of Jin. The men took 300,000 horses and were armed with catapults which could lob rocks or firebombs 100 metres.

Great empire: Under Khan's reign of terror the Mongol empire encompassed most of Asia

Behind this came herds of mares to provide the warriors with horse milk. Often this mass migration incorporated wives, families and sheep. The whole juggernaut probably ran to 250,000 with a million animals in tow.

When they reached a fortified city their strategy was to surround it, starve it and invite its leaders to surrender or be annihilated. Those that refused were slaughtered to the last man, woman or child, but the same thing might easily happen to those which capitulated.

Terror was the Mongols’ weapon — shock and awe. Genghis applied it ruthlessly. In 1219 he led his army westwards from China towards the ancient cities of Samarkand and Bukhara, the eastern outposts of Islam, which had a degree of civilisation undreamed of on the Mongol steppes.

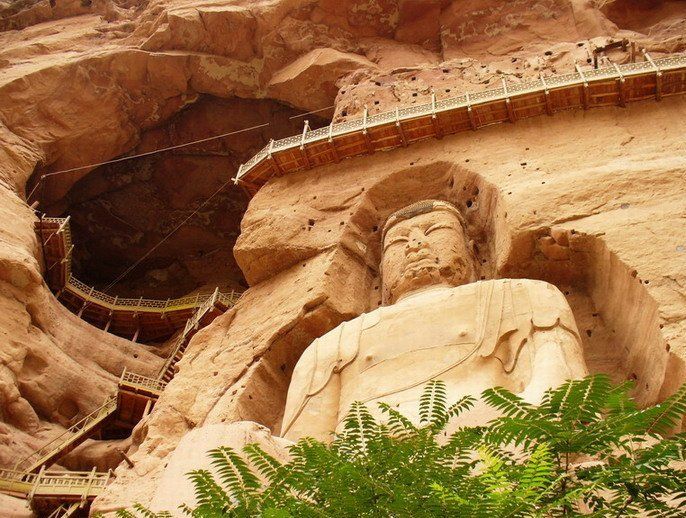

There they lay with domes, palaces, mosques, huge libraries and scores of scholars leading the rest of the world in maths, science, astronomy and general knowledge. Bukhara was stripped of its treasures, bombarded and burned until all the males ‘who stood higher than the butt of a whip’ had been killed.

The Mongol juggernaut rolled on towards Samarkand, defended by some 100,000 troops and 20 elephants, which panicked, trampled their drivers and made off into the plains.

When the city’s merchant leaders and senior clergy invited the Mongols in, they looted their treasures, their wives and helped themselves to such survivors as would make slaves.

They moved on to lay siege to the remaining great city, Gurganj. By the time victory came, five months later, the invaders ‘were in no mood for mercy’. The figures recorded by Muslim historians are staggering: 50,000 soldiers killed 24 men each.

DID YOU KNOW?

There were 40 sacrificial virgins slaughtered at Genghis Khan's funeral

Genghis now turned his attention to Merv, an oasis city of mosques and mansions. Its ten libraries contained 150,000 volumes, the greatest collection in Central Asia. The Mongols entered the city and after separating 400 craftsmen and a crowd of children to act as slaves, drove the remaining population on to the plain.

‘Then,’ writes Man, ‘the killing started. The place was ransacked, the buildings mined, the books burned or buried. Merv lost almost everything and almost everyone.’

The Mongols ordered that no woman, man or child be spared. Each soldier in the 7,000-strong army was allotted around 300 people to kill. Most had their throats slit. Others were led out, 20 at a time, to be drowned in a trough of blood.

You might have thought even the most hard-hearted troops would baulk at having to slit the throats of so many victims, but it doesn’t seem to have troubled the Mongols who would have despatched them, says Man, as easily as sheep.

Merciless: Some historians estimate that as many as four million people were killed by Khan's soldiers

The fearsome leader remembered: A 16ft Genghis Khan statue in Marble Arch, London

He points out that it takes only seconds to slit a throat, and that for 7,000 soldiers ‘the slaughter of a million would have been an easy two hours’ work’.

In the late 18th century the English historian Edward Gibbon placed the total slaughter at more than four million. The figure may be exaggerated, but it was certainly one of the biggest mass killings in history. Genghis then returned to northern China, which he had only partially conquered. By the second week of August 1227 he was on the verge of achieving an empire running from the Pacific almost to Baghdad.

It was not to be. He became seriously ill — possibly with typhus — and just days later was dead. But not before having told his leading captives: ‘I am the punishment of God. If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent me as your punishment’.

Throat slitter supreme: Khan, whose real name was Temujin, was named Genghis by his troops because of his fierce personality

His body was secretly taken back thousands of miles to Mongolia, where it was buried somewhere unknown on a sacred mountain. Today, a massive mausoleum shows its visitors colossal statues of him — but no body. They are still looking for it.

Did Genghis achieve anything but the Guinness record in bloodshed? John Man believes he had redeeming features. He allowed toleration of all religions — perhaps because he didn’t have much of one himself, except as a mandate for conquest. He allowed women to play a more leading role than other dictators and he employed anyone of talent, irrespective of where they came from.

But he built nothing. He left no palaces, no writings, no philosophy, nothing but territories that owed allegiance to him.

It is a relief to turn to his grandson, Kublai, for the rest of the book. Kublai had himself been recognised not only as the great Khan but as first emperor of a new Chinese dynasty, the Yuan.

He built his new capital, known as Shang Du, which was mistranslated by Coleridge in his opium-inspired poem, Xanadu. Kublai’s normal palace there was called the Pavilion of Peace but for summer he built the pleasure dome that we all know.

It wasn’t much like Coleridge’s dream. The sunny pleasure dome was not made on caves of ice. It was made of bamboo rods laid in a circle and supported by carved wooden columns.

One of his great innovations was paper money. He gave China a new legal system. He built pagodas and adopted Buddhism. Altogether he was a lenient dictator.

He grew very fat (the drink was to blame) and died at the age of 80. At this point he ruled from the Black Sea in the west to the China Sea in the east, covering a sixth of the world’s known land mass.

But within two years of his death this empire had split into its component parts, according to nationality. The Mongol Empire had vanished, leaving a legacy to the world of precisely nothing.

Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road

Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road

Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road

Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road

Protecting the city ruins along the Silk Road

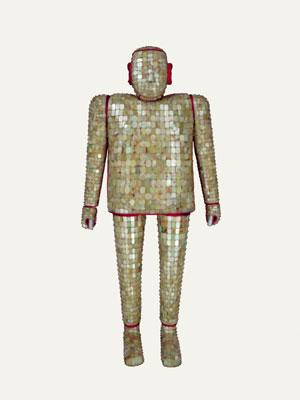

![A silver tiger, found in Shenmu county, Shaanxi province, is believed to date back to between the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) and the Han Dynasty.[Photo provided to China Daily] A silver tiger, found in Shenmu county, Shaanxi province, is believed to date back to between the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) and the Han Dynasty.[Photo provided to China Daily]](http://www.ecns.cn/2014/07-15/U363P886T1D124141F12DT20140715110237.jpg)

![A bronze pot unearthed from the tomb of Liu Sheng (165-113 BC), or, Prince Jing of Zhongshan, in Mancheng county, Hebei province.[Photo provided to China Daily] A bronze pot unearthed from the tomb of Liu Sheng (165-113 BC), or, Prince Jing of Zhongshan, in Mancheng county, Hebei province.[Photo provided to China Daily]](http://www.ecns.cn/2014/07-15/U363P886T1D124142F12DT20140715110148.jpg)